contemplations on "asian america"

I’ve been turning over in my mind what it means to be Asian-American, what it means to be an Asian in America, what it means to be a person of color, and how a slight tweak in phrase can transform the communication of one’s political and cultural identity.

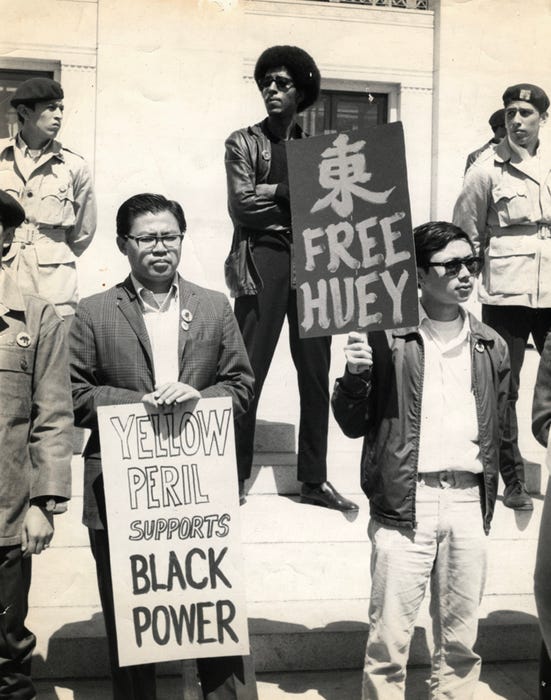

A refresher: the “Asian-American” identity was conceived in the 1960s (the height of the Civil Rights movement) by graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley. The aim was to cultivate an organization of political activists of Asian descent, taking inspiration from the Black Power movement and the protests against the Vietnam War. This newly formed Asian-American alliance organized alongside Black and Chicano student organizations on campus with an agenda of equality, anti-racism, and anti-imperialism1.

Asian-American was a radical label of self-determination, socially constructed as a political label, rather than a cultural or familial one.

In fact, immigrants originally who arrived in the United States from various countries in Asia (China, Japan, Korea, India, the Philippines, etc.) in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries did not see themselves as part of the same racial category, nor did they make mass attempts to form alliances with each other. As a single example of many, Chinese and Korean Americans often wore buttons stating their ethnicity so that they wouldn’t be mistaken for being Japanese during World War II. It’s worth noting that even since the 1960s, hate crimes have continued to occur against Asians in America including the killing of Vincent Chin in 1982, the 1992 LA riots, and the Atlanta spa shootings in 2021.

The Asian populace within America has substantially evolved since the Civil Rights movement, and I think it’s worth revisiting the purpose of a term like Asian-American both at a political and cultural level today.

Semantically, it’s unclear whether Asian-American or AAPI is meant to encompass East Asia, pan-Asia, American-born Asians, Asians immigrants in America, or any combination of the above. I once asked an ethnically Chinese friend of mine who grew up across the UK, Canada, and America whether he identified as Asian-American; he said no. He did, however, identify as AAPI which ironically stands for “Asian American Pacific Islander.” I admit that this is a bit of a silly example, but I have several anecdotes of this type of interaction, all usually ending with the conclusion that the “Asian hyphen” (ie: Chinese-Canadian or British-Indian) is a largely American phenomenon which I will unpack a bit later.

The Asian populace in America contains refugee communities, upwardly mobile Asians on skilled worker or student visas, American-born Asians whose families have resided in America for several generations, and many configurations outside and in-between. The variety of experience is particularly clear socio-economically. Over the past 50 years, “the gap in the standard of living between Asians [in America] near the top and the bottom of the income ladder [has] nearly doubled, and the distribution of income among Asians [has] transformed from being one of the most equal to being the most unequal among America’s major racial and ethnic groups.”

The colossal demographic/socio-economic differences within the Asian populace in America lead to an unsatisfactory, though perhaps not surprising, conclusion: a cohesive political identity around Asians in America (today) may not exist.

In fact, there is existential political in-fighting within the community, often engaging in an America-first ethnocentrism that may shed light on why Asian-Americans are so invested in a hyphenated label I mentioned earlier—it attempts to make their ambiguous place in the American project more clear.

From Andy Liu:

“[M]any politicized Asian-Americans struggle to locate their place within a US-centric black-white paradigm, wherein they must fit themselves into either the role of the oppressed ‘people of color’ or the role of the privileged white oppressor. Sometimes Asians choose option A, sometimes option B, but the end-result is usually something very confused. One consequence is that this does not open up a broader discussion about racism from multiple perspectives but instead encourages the assimilation of Asian diaspora (and Latino/a and Muslim, etc.) views into the norms and values of white liberals, namely, guilt and privilege-talk.”

Considering a lack of political cohesion, it’s fascinating that the need for “Asian representation” has become such an outcry in culture/media. Similar to the question of an Asian-American political identity, I wonder if an inclusive Asian-American cultural identity may hold water.

I can trace the influx of Asian media (predominantly East Asian) in America during my lifetime through phenomena like the Hallyu wave, Asian Youtubers like Wong Fu Productions and Jenn Im, the release of Crazy Rich Asians, and of course… the infamous love for cut fruit.

At first, Asian narratives in media felt like a breath of fresh air and grossly overdue. But like many things, it occurred slowly, then all at once.

I grew tired of the stinky lunchbox trope and cringed at phrases like “Asian representation.” I didn’t avoid these narratives in an assimilationist sense to become more White or in an effort to see beyond color, I was simply jaded by being fed these stories so repetitively. I couldn’t help but wonder whether annoyingly reiterating the same Asian tropes was the only way to be acknowledged in an economy fighting desperately for attention.

Hyun Kim articulated this well in their piece My Stinky Lunchbox Story:

“[A]ny time certain types of stories are being told over and over again to the point that it starts feeling like a trope, you have to ask why. What purpose do they serve and to whom? Who keeps soliciting and publishing them?”

I confess with a whisper that I fear the Asian-American identity has been pounded and molded into a clean narrative, one that can be politicized, targeted, marketed to, but in all actuality, isn’t very resonant or binding.

I resent the commodified solidarity of supporting Asian-American media/products that I don’t actually enjoy simply because “economic power is political power.” I guiltily contemplate whether the ability to “dislike” something Asian-American is a privilege in itself.

I question whether Asian-American as a political and cultural identifier even makes sense given the material differences we have yet to sort through and understand within ourselves—histories of oppression, imperialism, and a present state of massive inequality and political shaming.

I still fail to understand my friends who grew up in communities where “everyone was Asian.” I fail to understand my friends who were the “only Asian person in their entire school.” I fail to understand my friends who are here on a visa, hailing from countries all over the world.

I criticize myself for even continuing to use Asian-American and Asian in America interchangeably in this piece alone and for writing largely about East Asia.

Yet despite all this—the discomfort and uncertainty, the unsettling interrogation of an elusive Asian-American identity—and for reasons I continue to not understand, I still feel deeply Asian-American.

I still cried during the mother-daughter scenes in movies like Turning Red and Everything, Everywhere, All at Once.

I will still get “Oriental” tattoos because I don’t know how to put my feelings around my heritage into words.

I still wish someone, for the love of God, would gift me an Azuki NFT.

I will still eagerly go to every new Asian fusion restaurant opening in New York, and would eat dim sum every week if I could.

I will still happily attend every “Asians in X” event even if the X really has nothing to do with being Asian.

I will still gush over how nice it is to talk to people who “understand” anime and k-dramas.

I will still continue to love contemporary Japanese fiction and have read all the “modern Asian-American canon” like Minor Feelings by Cathy Park Hong, Sour Heart by Jenny Zhang, Exhalation by Ted Chiang, etc.

While I’m unable to articulate how all of these traits fulfill a greater narrative, they still fulfill my own identity, and I guess the journey now is learning how to accept that tension.

A few weeks ago, I got off the subway in Brooklyn and was approached by a young Chinese girl (unverified but I could just tell). She asked me for directions to the local college so she could attend a scheduled SAT prep class.

In most cases, I would’ve just done my best to dictate the directions and gone on my way, but upon noticing she didn’t have a phone, I decided to accompany her, just to make sure she got there safely. On the walk, she told me about how she was excited to graduate high school and get out of New York, how she had begged her parents to let her attend this SAT prep class by herself (I, personally, took the Kaplan online course back in my day).

I closely identified with that girl during that short encounter despite not even knowing her name and the fact that we grew up in entirely different environments (her in New York and I in suburban Georgia); I’m still not entirely sure what Asian-American identity or solidarity means to me but somehow, those few moments felt as close to an understanding as I could reach.

thank you Nikhil, June, and Austin for your thoughtful edits and care <3

At the time, multicultural political alignment was a blooming national movement, a key example being the Rainbow Coalition.